The Problem: Racism is hazardous to the health of pregnant people and their infants

Public awareness about the devastating impacts of systemic and interpersonal racism has increased sharply with the escalation of racist violence and the COVID-19 pandemic’s disparate impact on communities of color. The Black maternal and infant health crisis is emblematic of how the experience of being Black in the United States undermines health regardless of socioeconomic status. Leading experts and advocates underscore that it is racism, not race, that drives these inequities. Researchers, decisionmakers, and advocates have increased their focus on the role that the social determinants of health have on communities’ health and well-being, especially in the area of maternal and infant health.

To be sure, understanding and addressing the role of structural racism in the maldistribution of health risks, resources, and assets that systematically disadvantage Black, Latinx,* Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, American Indians and Alaska Natives are essential to achieving optimal health for all. However, to forge a path forward that eliminates the undue burden of disease and early death that communities of color carry, our understanding of racial and ethnic health inequities must include how the experience of living in a body that is the target of racism not only takes a psychological toll but directly damages a person’s physiology, including their DNA. The physiological impact of racism on black and brown bodies is especially evident in the health of pregnant people** and their infants.

Science is catching up to the truth communities of color have known for generations: that experiencing racism throughout one’s life course damages one’s long-term health. “Race” is not the cause of these inequities. Race is a social construct; there is no gene or cluster of genes that belong to any racial group. It is not “Blackness,” “Indianness,” “Latinaness,” or “Asianness” that makes people sicker and shortens their lives, it is living in a country rife with structural and interpersonal racism. Structural racism heaps environmental, economic, and social risks on communities of color, while keeping white neighborhoods safer. Communities of color are stripped of the resources needed to protect themselves and be healthy, as white neighborhoods as close as just one zip code over enjoy health sustaining assets – from better schools, to clean water and air, to safe streets and parks and playgrounds. The exploding interest in addressing social determinants of health is based on addressing these inequities.

Science is catching up to the truth communities of color have known for generations: that experiencing racism throughout one’s life course damages one’s long-term health. “Race” is not the cause of these inequities. Race is a social construct; there is no gene or cluster of genes that belong to any racial group. It is not “Blackness,” “Indianness,” “Latinaness,” or “Asianness” that makes people sicker and shortens their lives, it is living in a country rife with structural and interpersonal racism. Structural racism heaps environmental, economic, and social risks on communities of color, while keeping white neighborhoods safer. Communities of color are stripped of the resources needed to protect themselves and be healthy, as white neighborhoods as close as just one zip code over enjoy health sustaining assets – from better schools, to clean water and air, to safe streets and parks and playgrounds. The exploding interest in addressing social determinants of health is based on addressing these inequities.

However, although researchers have studied the impact of experiencing racism, trauma, and other kinds of adversity on the health of people of color, most have focused on individuals’ behaviors as a higher risk of engaging in unhealthy behaviors – without considering the availability of options. It is the difference between making good choices and having good choices. Still, there is an even deeper level of impact that racism has on an individual’s health that must be understood – particularly in the context of maternal and infant health: how experiencing the toxic stress of racism affects physiological processes.

Racism causes biological damage on people who experience it

Researchers have identified a number of pathways through which racism and other forms of toxic stress and trauma directly impact biological processes to the detriment of a person’s health. Allostatic load is a central concept in understanding the general phenomenon of “wear and tear on the body” that accumulates in response to repeated or chronic exposure to stress. In a nutshell, when encountering stress, the body reacts with a fight, flight, or freeze response that includes a flooding of adrenaline and cortisol, an increase in heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure, among other phenomena. This adaptive response is important for human survival. Usually, when the stressful situation is over, the body returns to normal. But if the stress is repeated or constant (as is the case with racism) the body does not have the chance to return to the pre-stress state and it becomes a maladaptive response, affecting the neuroendocrine, immune, autonomic, and cardiovascular systems. Allostatic load is a measure of the combined biological manifestations of chronic stress over the life course, which has been directly linked to poor health. It is the physical impact of living in a constant fight-or-flight state, or as some have observed, post-traumatic stress without the “post.”

Another foundational concept in the study of racism’s biological impacts is weathering, which was originally coined to describe how Black people’s bodies become “worn down” over time by the cumulative impact of racism, increasing their vulnerability to illness and disability. In addition, researchers have shown how social adversity is linked to increased inflammation and reduced resistance to viral infections, which is associated with the development of chronic diseases.

Research on the negative impact of racism and chronic or toxic stress on health via physiological pathways includes the following illustrative findings:

- Among Black people, exposure to racial discrimination and segregation in childhood was more predictive of inflammation in adulthood than the traditional risk factors of diet, exercise, smoking, and low socioeconomic status, and also amplified inflammatory effects of race-related stressors as an adult.

- Black women between the ages of 49 and 55 were found to have a biological age 7.5 years older than white women of the same chronological age, as measured by telomere length in their DNA, a bio-measure of aging.

- Pregnant Black women showed a significantly greater inflammatory response to stressors compared to pregnant white women, as measured by levels of interleukin-6.

- In a study of cardiovascular reactivity in response to a stressor, Black participants showed higher increases in blood pressure and heart rate and longer recovery times compared to white participants.

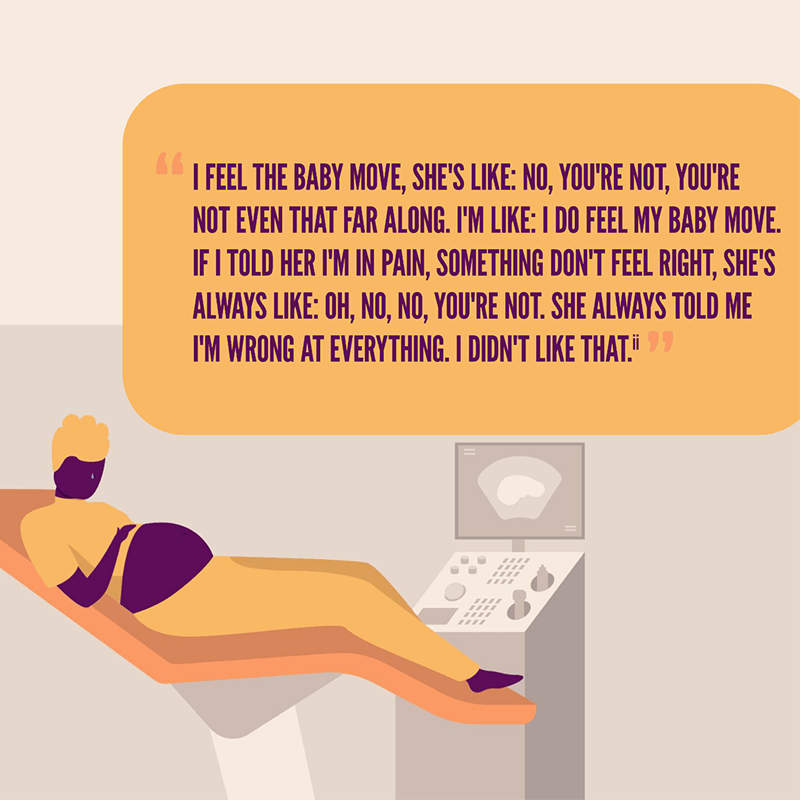

Racism hurts the minds and bodies of moms and babies

The physiological impacts of racism on bodies are particularly evident for pregnant people and their infants. The growing field of epigenetics examines the changes in gene activation and deactivation produced by our environment and exposures, including during fetal development. While those changes do not affect the underlying DNA sequence, they are heritable, and can be heavily influenced by environmental stressors. This can help explain how when a birthing person experiences racism, it can have a direct physiological impact not only on themselves, but also on their infant, generating inequity even before birth and perpetuating a vicious cycle that can last for generations. Therefore, racism is even more dangerous when considering the dyad of health of childbearing people and their infants.

A systematic review of research studying the links between chronic stress and physiological changes among Black pregnant women showed that Black women’s experience of interpersonal racial discrimination during pregnancy affects physiologic biomarkers relating to cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, and immune systems that indicate increased stress and have been linked to poor maternal health, with clear potential to impact the infants’ early and longer-term health.

A systematic review examined the relationship between maternal experience of interpersonal discrimination and both gestational age at birth and birth weight.

- Nine of 13 U.S.-based studies found a negative effect of interpersonal discrimination on preterm birth or gestational age at birth.

- Ten of 13 U.S.-based studies found a negative effect of interpersonal discrimination on birth weight.

Additional studies have shown the links between experiencing racism and discrimination and adverse birth outcomes.

- Chronic worry about racial discrimination is linked to preterm birth in Black women.

- Black birthing people exposed to racism in the year prior to giving birth were more likely to have an infant with low or very low birth weight.

- A multi-year study covering more than 2 million Black women found a direct relationship between increases in area racism (as measured by the proportion of internet searches of the “N-word”) and increases in preterm birth and low-birthweight infants.

- Infants born to Latina mothers living in Iowa after a massive immigration raid in the state were at a 24 percent (for foreign born mothers) and 21 percent (for U.S. born mothers) greater risk of low birth weight compared to similar babies born a year earlier, regardless of the mother’s citizenship, country of origin, or proximity to the location of the raid.

- A California study found birthing people of Arab descent and those with Arabic names experienced increased violence, harassment, and other discrimination immediately after September 11, 2001, and significantly higher rates of preterm birth and low birth weight in the six months following 9/11, compared to similar women who gave birth a year earlier.

Recommendations

- Congress must incorporate the Health Equity and Accountability Act (HEAA) into upcoming health care legislation, to provide the tools needed to address health inequities and ensure that eliminating health and health care disparities are prioritized.

- Federal, state, and local policymakers must mandate and support the standardized collection and reporting of health and health care data that is disaggregated by race and ethnicity, including subgroups, and the stratification of measures and outcomes.

- Federal, state, and local decisionmakers must provide upfront funding to support the establishment and functioning of community-led and -based models of reproductive health care that provides respectful, trusted, culturally congruent care and support grounded in reproductive justice and that incorporate non-clinical providers such as doulas, promotores, community health representatives, and other community health workers, including peers.

- Federal and state decisionmakers must require all health care payers to cover reproductive health, maternity, behavioral, and primary care by community-led and -based providers, including in birth centers.

- Federal decisionmakers must add reducing racial and ethnic health inequities to Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s charge and direct the agency to develop, pilot, and evaluate maternal- and infant-health-specific models that focus on mitigating the effects of racism and include person-reported measures of respect and dignity.

- To reduce health inequities in medicine, every health care institution of learning must design, tailor, and prioritize anti-racist curricula for all educators, including clinicians who provide training for medical, nursing, doula, and midwifery students and other support personnel.

- Congress, state, and local policymakers must require all health care providers and their staff (as appropriate) to receive regular trainings on mitigating implicit bias and structural racism, the effects of chronic stress, trauma, and allostatic load in communities of color, and trauma-informed care.

- Educators of maternity care clinicians and of doulas, lactation, and other support personnel must prioritize developing a maternity care workforce that resembles the demographic makeup of birthing people.

- Researchers must work with communities to continue to study the effects of racism on maternal and infant health outcomes, strategies to foster increased resiliency in individuals, families, and communities harmed by racism, and how improved maternal and infant care can reduce inequities.

*To be more inclusive of diverse gender identities, this bulletin uses “Latinx” to describe people who trace their roots to Latin America, except where the research uses “Latino/a” and “Hispanic,” to ensure fidelity to the data.

**We recognize and respect that pregnant, birthing, postpartum, and parenting people have a range of gender identities, and do not always identify as “women” or “mothers.” In recognition of the diversity of identities, this report prioritizes the use of non-gendered language where possible.