The Problem: Violence against pregnant people inflicts lasting harm on them and their babies

Intimate partner violence (IPV) – also commonly referred to as domestic violence – is endemic in the United States, with nearly one in three women experiencing physical violence by an intimate partner over their lifetime. IPV can also include emotional, sexual, and economic abuse. More than one-third of women report psychological aggression by an intimate partner, and nearly 20 percent report sexual violence by an intimate partner during their lifetime. In addition, financial or economic abuse occurs in 99 percent of cases where other forms of IPV are also present. Early evidence indicates that cases of domestic violence have increased, and become more severe, during the coronavirus pandemic.

IPV negatively affects people’s lives in multiple short- and long-term ways. Current or former intimate partners kill, on average, three women every day, and those who survive IPV often suffer a wide range of physical and mental health problems caused or exacerbated by the violence. These include, for example, physical injuries (including gynecological harm), asthma, gastrointestinal problems, and chronic pain, as well as mental health conditions like anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Additionally, IPV has broader, pervasive effects over the survivor’s lifetime, including, but not limited to: housing instability and homelessness, unemployment, loss or delay of educational opportunities, food insecurity, financial instability, and unwanted entanglement in civil and criminal legal systems.

IPV negatively affects people’s lives in multiple short- and long-term ways. Current or former intimate partners kill, on average, three women every day, and those who survive IPV often suffer a wide range of physical and mental health problems caused or exacerbated by the violence. These include, for example, physical injuries (including gynecological harm), asthma, gastrointestinal problems, and chronic pain, as well as mental health conditions like anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Additionally, IPV has broader, pervasive effects over the survivor’s lifetime, including, but not limited to: housing instability and homelessness, unemployment, loss or delay of educational opportunities, food insecurity, financial instability, and unwanted entanglement in civil and criminal legal systems.

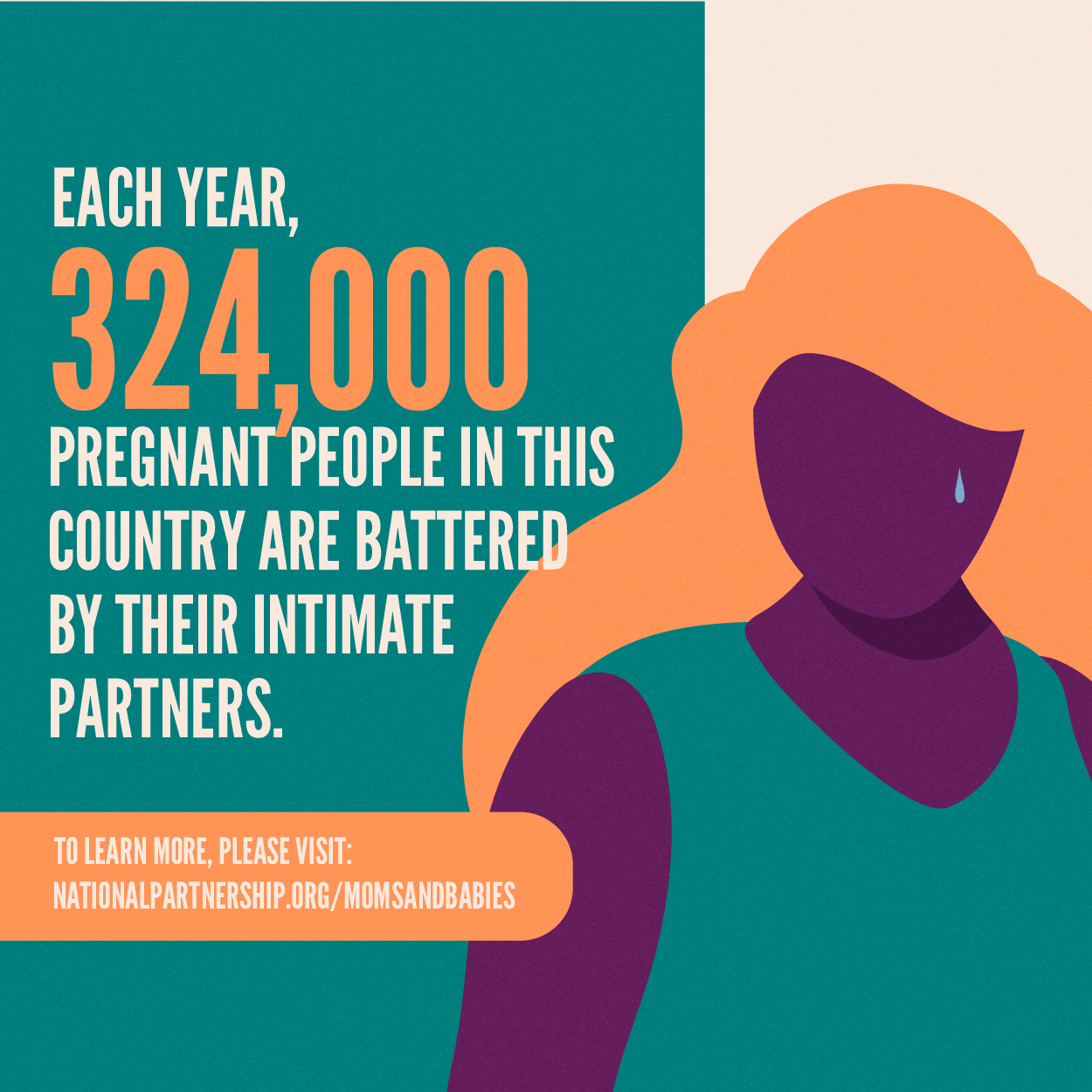

Pregnancy can often be an especially risky period for IPV, as many women report that abuse started or intensified when they became pregnant. Each year, an estimated 324,000 pregnant people in the United States are battered by their intimate partners. IPV during pregnancy can hurt both maternal and infant health. Furthermore, even though domestic violence is more common among pregnant women than are other conditions for which they are routinely screened – such as gestational diabetes or preeclampsia – few providers screen pregnant patients for abuse.

Intimate Partner Violence Increases Risk of Pregnancy Complications And Poor Health for Moms and Babies

Systematic reviews (rigorous reviews that collect, assess, and synthesize the best available evidence from existing studies) have found:

- Women who are abused during pregnancy are more likely to receive no prenatal care or to delay care until later than recommended.

- Women experiencing domestic violence during pregnancy are three times more likely to report symptoms of depression in the postnatal period than women who did not experience domestic violence while pregnant.

- Maternal exposure to domestic violence is associated with significantly increased risk of low birth weight and preterm birth.

- Women who experience IPV during pregnancy are about three times more likely to suffer perinatal death than women who do not experience IPV.

Other individual studies have found that:

- 63 percent of female homicide victims were killed by an intimate partner, in cases where the victims knew the offender. Homicide is a leading cause of traumatic death for pregnant and postpartum women, accounting for 31 percent of maternal injury deaths.

- Infants exposed to IPV can show signs of trauma, including eating problems, sleep disturbances, higher irritability, and delays in development. These harms can be mitigated by the presence of a secure relationship with a safe caregiver.

Black, Indigenous, and Other People of Color Are Disproportionately Harmed by Intimate Partner Violence

Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) people suffer the impact of IPV disproportionately, particularly considering that these communities tend to have less access to the care and resources that would prevent, mitigate, and remedy the effects of IPV. Available reported data appears to indicate a higher rate of IPV in some BIPOC communities. However, those statistics must be understood in their broader context, including the impact of socioeconomic deprivation, the effects of interpersonal and systemic racism, the over-policing of many of these communities, and that people with more resources are often able to keep IPV a “private matter” under the radar of authorities. What is clear is that whatever the actual prevalence of IPV among BIPOC people, its harm is compounded by the inequities survivors face in accessing health care and other economic and social supports they need for themselves and their families.

- 45 percent of Black women report physical violence, sexual violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime, which is almost 20 percent higher than the rate reported by non-Hispanic white women.

- 48 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native women, report physical violence, sexual violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime, which is more than 25 percent higher than the rate reported by non-Hispanic white women.

- Compared to their white counterparts, Black women survivors of IPV have higher rates of depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation or suicide attempts.

- Research also indicates that factors related to socioeconomic and immigrant status negatively impact survivors’ physical and mental health outcomes.

- Black and Latina survivors are less likely to seek physical or behavioral health care for their IPV injuries, compared with white survivors. Reasons for not seeking care include lack of insurance coverage or affordable health care, distrust of providers, historical and ongoing racism and trauma, fear of discrimination, and barriers due to immigration status.

Recommendations:

- Federal and state level decisionmakers should require and provide resources for both individual and institutional health care providers to consistently screen all pregnant and postpartum people for intimate partner violence, receive training on providing trauma-informed care, and offer warm referrals to community-based, culturally and linguistically appropriate services for people that need them.

- Federal and state level decisionmakers should require all health care provider institutions and organizations to develop and implement institution-wide, survivor- centered, trauma-informed protocols for assessing and responding to IPV, both among their staff and their patients.

- Congress should reauthorize, expand, and increase funding for the Violence Against Women Act and the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act to better meet the needs of survivors, especially those from communities affected by structural racism and other inequities.